Andy’s Story

2004

Life was going well – I had two gorgeous children aged 5 and 6, a lovely home, great friends, and a husband who was doing really well in his chosen career as an accountant. I had also just started a three-year University degree studying dental therapy and hygiene: something I had always wanted to do. I knew it would be tough but I had good friends, family and a loving husband to support me. Not long after starting my course my husband Andy (34 at the time) began getting very tired and needed to sleep much more than usual. We put it down to stress at work initially. However some other factors were starting to show.

Andy and I enjoyed going out with friends and generally having a good time. We both enjoyed a drink and did on occasions suffer the odd hangover the next day. After a few nights out with friends, Andy seemed to have very bad reactions to alcohol the following day; he also started suffering from headaches and a cold seemed to last for weeks. Andy had also lost the ability to communicate effectively in public and I found myself speaking for him, as it was easier and he preferred it that way. I remember one day we went into town to buy him a new suit for work. I finally realised how bad the situation had become when the shop assistant asked me if he was allowed pinstripe! I remember thinking, “she thinks I’m dictating what he can and can’t wear”. He had gone from being a confident, lively, opinionated man to a recluse who lacked the energy to drive to work or to go for a walk. He adopted the nickname “sit on the fence Andy” amongst his friends due to his lack of enthusiasm to join in conversations or to have his own opinion. After many visits to our GP, all the blood tests came back normal and it was suggested that maybe Andy was suffering from depression or Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), also known as chronic fatigue syndrome. I encouraged Andy to take vitamins in an attempt to help the situation as we both knew there was nothing in our lives for him to feel depressed about; it was upsetting me a great deal.

Easter Half term 2005

In an attempt to help the situation we decided to take the children to Centre Parcs in Nottingham (a three hour drive from Hampshire). Andy was fine with this but asked me to drive as he was feeling tired. We loaded the car with kids, bikes and kitchen supplies and set off. The kids and I had a great time swimming, cycling and playing out doors. Andy hardly moved all week.

When it was time to leave we packed up the car. I needed a hand to put the bikes onto the bike rack, which Andy helped to do. It was then that I noticed the right side of his face had drooped to one side. At the same time Andy complained of a tingle in his right hand. I went into a state of panic; I thought he was having a stroke, although it is normally the left side of the body, which is affected, not the right. Here we were with two young children stuck in the middle of the forest.

There was a medical office located by the park entrance, which was manned by a nurse. After being told a doctor could see him at 5pm at the local village surgery (5 hours hence), we decided to drive 3 hours down the motorway to our own GP. I rang ahead to warn them we were coming with the intention of driving straight to the local A&E if the situation worsened before we made it home. All the time Andy was trying to convince me that he felt fine and I was worrying unnecessarily. As I drove down the M1 adrenaline pumped furiously around my body. Added excitement occurred as I looked in my rear view mirror and saw my daughter’s Barbie bike slipping off the bike rack!

Three hours later we were sitting in the surgery with our GP still having no idea what was wrong with my husband. As a last resort Andy was referred privately to Chris Gordon, a General Physician in Winchester.

This chap was really on the ball. He performed various tests to assess for motor skills and general well being. He authorised a thorough eye examination with an ophthalmologist, an ultrasound to check internal organs and an MRI scan.

2nd April 2005

The appointments were set up within a week; the results of the eye test were fine, the results of the ultrasound showed a possible enlarged spleen (the function of the spleen is to hold reserve blood for the body, quite appropriate when you consider he was about to discover a tumour). The MRI scan was performed at 5pm the same afternoon and within a few minutes the radiographer took us into a small room and told us that Andy had a Primary Malignant Brain Tumour.

My initial reaction was sheer disbelief “there must be some mistake”. I remember even asking him if he was sure it wasn’t something else! The radiographer left the room and we were both speechless. What now?

We had a follow up appointment with Chris Gordon at 6.30pm that evening that confirmed the news that this was a primary malignant brain tumour and he showed us the tumour size on the scan. The tumour was about the size of an orange located in the left frontal region of the brain. It was so large that it had squashed the brain over to right hand side of the skull. Chris Gordon was extremely supportive and talked us through possible options; i.e. surgery, radio and chemotherapy. He prescribed steroids to try to reduce the tumour in size prior to surgery. I remember feeling very shocked that they could tell immediately that it was malignant. The next step was to arrange an appointment with Mr Sparrow the Neurosurgeon at Southampton General, which was done the next day.

3rd April 2005

Mr Sparrow (who by the way we now name God) was fantastic. After viewing the scan he performed a few small checks to test for strength and memory. Memory was one thing with which Andy had been experiencing difficulties. He explained the options and said he could remove it on Saturday. He gave us no statistics but instead dealt straight with the facts, which I liked and made it sound like this was a very routine procedure. The five days prior to the operation were the worst five days ever. We tried to do things to take our minds off what was happening but it really didn’t work.

We decided to take the children ten pin bowling one day but had to stop half way through. We were always very honest with the children and sat them down to explain that daddy has a naughty tumour growing in his head, which the doctors have to get out. They took it well as I guess they were aware that daddy had been poorly for some months now.

9th April 2005

The day of the operation arrived and I remember driving to the hospital at 7am in the morning just to be with Andy prior to surgery. I went all the way down to the doors of the operating theatre with him, hugged him and told him to make sure he woke up when it had finished, then turned around and burst into floods of tears. My biggest fear was that he would wake up and not know who I was. I then pulled myself together (as women do) and drove home.

My family and friends however were not too keen about me being on my own that day and insisted on phoning every half an hour to check on me. All I wanted to do was spring clean the house (I guess it was my way of coping). At 1pm I called the hospital and was told Andy was out of surgery and in recovery. It is a little shocking when patients are brought up from theatre if you are not sure what to expect as there are various monitors, tubes and drains connected to the body. The one thing that I wasn’t keen about was the drainage tube coming from the head! Still he wasn’t alone – there were many patients in similar situations on the ward. One of the most shocking things I experienced when Andy was in hospital was the fact Mr Sparrow had used staples to secure the wound after surgery. Believe it or not, prior to surgery Andy was really squeamish and did not like anything to do with blood or hospitals. The nurses failed to warn me the dressings had been removed a day or two later (luckily I was not squeamish). As I entered the ward I noticed forty staples sticking out of my husband’s head (just for the record not all surgeons use these). “Oh!” I exclaimed, “The bandages have been removed then!”

Andy seemed to be recovering well (all be it there was some fluid still present around the site of the operation) Mr Sparrow felt the craniotomy went very well although part of the tumour was very close to an area of the brain which affected speech and it was therefore decided to leave a small amount in for fear of permanent damage. The tumour was sent away to be analysed as Mr Sparrow reported that it looked fairly un-usual and considered that maybe it wasn’t malignant after all.

Andy was fortunate enough to be given his own room at the general with phone access. At 4am my home telephone rang. “Hi. It’s me, I can’t sleep”. It was Andy. He told me he knew what was causing the fluid build up in his head. I listened with interest (as you do at 4am in the morning). Andy told me that the excess fluid in his head was caused by the tumour still draining and exiting via the pores in his skin. Although I was half asleep I was a little concerned by this irrational statement. The next evening I received a similar phone call. This time Andy was cross because he wanted more food. He was still not sleeping but had obviously met another patient in a similar situation and the two of them stayed up all night discussing their futures.

When I visited him the next day I was concerned when his obvious hyper-activity had not reduced at all and Andy told me that a stain on the ceiling was blood dripping through from the ward above. I decided to casually mention my concerns to Mr Sparrow who immediately diagnosed this condition as steroid psychosis (a severe reaction to steroids); this occurs every so often in some patients. It totally freaked me out. Bear in mind I still did not know if this was a permanent effect from the operation! The steroids were stopped immediately and gradually after about a week Andy returned to normal and stopped verbally abusing the nurses and making irrational demands and telephone calls to everyone telling them how great he was feeling. Andy also came to the end of his packet of anti-convulsants (Phenotoin) and stopped taking these too, to the surprise of the consultant.

It took some time for the pathology results to come back from the lab. Eventually Mr Sparrow concluded that the tumour was in fact a low grade (non-anaplastic oligodendroglioma) and not as malignant as initially thought. Andy was told that no follow up therapy would be necessary and a routine scan would be done in six months to see how the remaining part of the tumour was behaving.

It took a few months of recovery at home but every week that passed Andy was becoming strong enough to go for walks, do jigsaw puzzles and paint. Reading took a little longer due to the concentration needed. Andy really began to re-evaluate his life and spent lots of time with our children and managed to attend school plays, concerts and parents’ evenings something that normally he would have been too busy to do. Andy and I were closer than ever and it really makes you appreciate how much they mean to you when there is a chance you could loose them.

August 2005

Andy returned to work and although still feeling a little tired, has managed to continue with the day-to-day running of his business, advising people with their businesses and financial matters. With huge amounts of support and help from family and friends I had also managed to continue with my degree.

November 2005

We decided to take a family holiday to celebrate Andy’s recovery. However a fortnight before we due to leave Andy suffered a grand mal seizure in his sleep (the first one ever). This was a shock to us all and a date was arranged for a CT scan and Andy was prescribed Phenotoin in case of any further episodes. I discussed the worst-case scenario with our GP. Due to being first aid trained myself she gave me some rectal diazepam to administer if a further seizure occurred and lasted longer than 5 minutes (l don’t think Andy dared to have another seizure knowing that I had the diazepam preparation at hand). We decided to go ahead with the trip anyway.

December 2005

We were told that the tumour had started to re-grow which could have been why the seizure occurred. Andy was then referred to Dr Sharpe (oncologist). It was decided that the best cause of action was to treat the tumour with radiotherapy. It was fair to say that the tumour was now in fact a grade 3 anaplastic type.

January 2006

Andy began three months of treatment Monday to Friday. Occasionally patients are able to continue working while undergoing radiotherapy but when it involves the brain it does seem to be more tiring, so unfortunately Andy was unable to work whilst having this treatment. The effects from the radiotherapy were hair loss and also burning to the side of the head. We told the children daddy now had to have some laser beam treatment to zap the naughty tumour.

May 2006

A further scan was then performed a couple of months after completion of the radiotherapy. The delay in the scan was to ensure that the inflammation was reduced. The scan results were positive, the entire tumour had now gone and Andy and I were told to get on with the rest of our lives. I cannot tell you how relieved were both were to hear this news.

October 2006

For the next few months we continued with our lives and during this time Andy felt he would like to perform a sky dive. One cold October afternoon Andy along with a couple of mates made a tandem jump off of Salisbury Plane. This charity jump raised over £2000 for “The children’s brain tumour trust” – Nottingham University, making Andy their biggest single-handed fundraiser.

January 2007

A year on and almost all of Andy’s hair has re-grown (all be it darker than it was). If I am honest the only long-term effect Andy has is short-term memory loss, although Dr Sharpe believes it is a man’s prerogative to have selective hearing! The thing that bothers Andy the most is that the DVLA will not allow him to drive a car due to risk of seizure for at least two years. I feel it is a small price to pay considering what might have been. We are now planning to take the family to Florida this year and to move house.

This is where I wanted to leave the story in February 2007 when I read

about Megan Jones. Unfortunately there is more…

February 2007

Andy has recently been suffering from minor dizzy spells (he describes it as an out of body experience). These last about 30 seconds and then he is fine. We decided we should mention this to Dr Sharpe who authorised a CT scan and a blood test to check his Phenotoin levels. The blood test showed that the Phenotoin levels were indeed a bit low. Dr Sharpe thought the dizziness might be petit mal seizures just breaking through the Phenotoin barrier.

Meanwhile we have just heard that the CT scan has shown some brightness indicating the beginning of tumour re-growth. Andy will probably need to start on a course of chemotherapy tablets. So this is where I end our story for now. There is never a dull moment in our lives, just the next challenge for us and we have every intention of beating this too.

March 2007

Chemotherapy has changed over the years; the latest and most exciting treatment to date is temodal (temozolomide), which Andy was given for a few months with little side effects. A further scan some months later revealed the tumour seemed to have shrunk.

May/June 2007

Andy and I always looked for opportunities to take the family away on holidays. This particular year we decided to take our extended family and friends to Florida. Sixteen people in total holidayed for three weeks and we all had a blast. Andy was allowed a month off the chemo and his energy levels went up tremendously. Putting aside our mundane tasks I always believe that at the end of the day its the memories are the most important.

July 2007

With the holiday over it was back on the chemotherapy, this time PCV on a 6 week cycle, which produced more side effects, namely constant vomiting. Dr Sharpe and the team had concluded that the Temodal had done as much as it was going to do at this time and that the PCV would be of more benefit to Andy.

October 2007

Despite the vomiting Andy still managed to work and started to play veterans football for our local village football club. A few weeks later however Andy suffered a bang on the head playing football, which put him in hospital. This prompted another scan. The scan revealed further tumour growth. Dr Sharpe and the team concluded that the PCV had failed to have the desired effect. Andy was therefore put back on the Temodal therapy.

March 2008

Christmas came and went during which Andy was given a short break from the chemo allowing quality time with the family. By the time Easter was nearly upon us Andy did not appear to be well in himself. Despite Andy telling me he was fine I decided to take it upon myself to call our neuro-oncology nurse and explain his symptoms. Fatigue, minor facial seizures lasting up to 4 minutes, confusion and of course memory problems. All these symptoms prompted a response from the neuro-oncology team and Andy was admitted to hospital. Andy’s symptoms became worst and he drifted in and out of consciousness the week or so prior to surgery.

Andy under went a second operation on March 25th – this time an awake- craniotomy, with gliadel wafers. Andy does remember parts of the operation mostly buzzing and sucking noises in his head but no pain. Mr Paul Grundy (neuro-surgeon) said that Andy actually started to recover during the surgery. A few days later, looking and sounding extremely well, Andy was discharged.

April 2008

Andy was doing really well and had no obvious side effects from the surgery. The histo-pathology unfortunately revealed that this tumour had now changed to a rare gliosarcoma grade IV (the most aggressive type). We knew the prognosis was not good (anything from 3 months to 1 year) but I felt we had been given another chance. Andy was put back on Temodal and Dr Sharpe requested to see him every 4 weeks.

Andy felt more confident than ever that he would beat this tumour and refused to believe he only had 1 year to live. The rest of the family meanwhile were coming to terms with the fact he may only have 3 months remaining. I instigated memory books, boxes and keepsakes for the children and tried to persuade him to make a short film for the children. I now realise that was one of the most difficult things I could have asked him to do. To try and sum up a life and to put recordings in place for events such as starting senior school or graduation, wedding day, first child. These are all things we would love to have an input on for our children, but how do you record a message to express the happiness you feel about the situation but the sadness you feel at not being there. Andy wrote us all a letter when he was feeling able to and hid it away, which was enormous comfort when we discovered it.

We decided to do what we do best which was to go on holiday again. After receiving the ok from Dr Sharpe we booked 2 weeks in Barbados from the 12th -26th May. Andy was advised to take antibiotics with him in case of an infection; we also knew seizures were still a possibility.

May 2008

Barbados was beautiful and for the first 5 days we snorkelled with the turtles, we raced on the beach, we hired jet skis and ate in some really nice places.

Then on the 16th May Andy suffered a large cerebral bleed. Nothing really prepares you for the inevitable.

Andy slipped into a coma that evening and never regained consciousness. He was able to hang on for his sister and his mother to fly out and say their goodbyes. They say the last thing to go is the hearing; the children and I all managed to say goodbye and tell him what a wonderful husband and father he had been and remember what a wonderful and active life he had led.

Andy died peacefully in St Michael’s hospital Barbados on 19th May and was given the best care and attention that he could’ve hoped for. Andy was flown back to the UK and was buried in Alresford, Hampshire. The sadness will always remain but so will the many happy memories we shared together. Life is so short: we really must enjoy each day as if it is our last. I feel fortunate to have been prepared to lose my husband, as many live their lives wishing they had the opportunity to say goodbye. Nothing or no one will ever replace the love that we shared together but life does move on and they say time is a great healer.

Andy Petersen

20.01.1970 – 19.05.2008

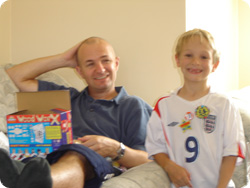

Pictured above with wife Julie, Jamie (aged 9) and Gemma (aged 8)

Over 300 family, friends and colleagues attended Andy’s funeral.

A final thought (not for cynics)

I believe God never gives us anything he feels we cannot cope with in life; there must be an ultimate reason why some of us suffer cancers and tumours and others do not.

From a spiritualist point of view, it is believed that to discover a cure one often must experience the disease first hand. Maybe those of you with tumours and cancers are really research scientists on the other side? Then there are those of us like myself who are put on this earth with a purpose to help, support, council or care for others in their hour of need.

Do not be afraid to ask God or our guardian angels for help I strongly believe they have helped me and are continuing to do so.

For any carers or parents reading this, know that it was never your fault and nothing would have prevented this from happening so please do not beat yourself up for the rest of your life; your loved one would not have wanted this.

My final word is really to reinforce positive thinking; it is never a bad thing to live each day as if it were our last however, never lose faith in your ability to get better. One day there will be a cure.

God Bless X

Email me at juliepetersen790@msn.com

With brainstrust, you are never alone. Click here to get in touch with one of our trained volunteers who has been through the same experiences you are going through.