Grief and bereavement

Death is nothing at all

I have only slipped away into the next room

I am I and you are you

Whatever we were to each other

That we are still.

Canon Henry Scott Holland, Death is Nothing at All

The concept of death

To love someone inevitably holds you hostage to fortune, because bereavement is a universal and integral part of our experience of love. If you commit yourself to love, then unavoidably you are also committing yourself to pain. The alternative is to never to love and that is to shrink from the test of being human at all.

When we lose someone we love we have lost intangibles, childhood, innocence, unconditional love, our insurance against mortality. We are thrown into chaos and loss. We need to remind ourselves that ‘sorrow is not a state but a process. It needs not a map, but a history’ (A Grief Observed, Lewis, 1961).

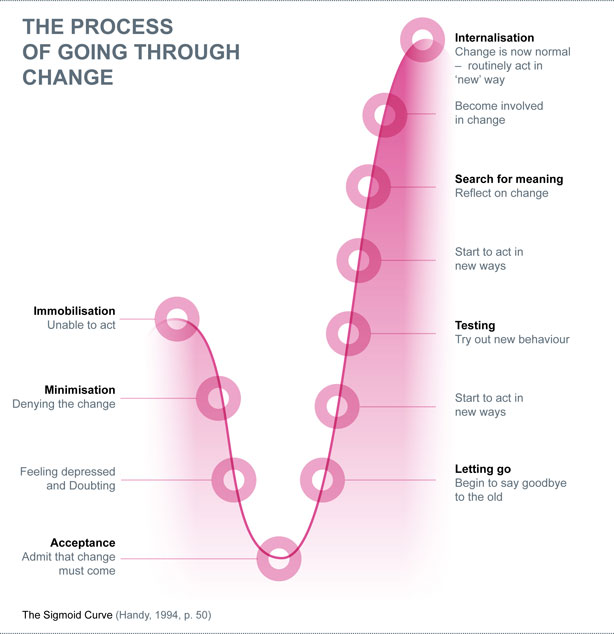

The Sigmoid curve identifies the emotions that we experience in change and helps us to understand our feelings. We can almost forecast what we will be feeling next, but no time scale can ever be applied. C.S. Lewis comments on the laziness of grief, ‘that initial lethargy where everyday routines, even the uncerebral, become mountainous obstacles.’ He continues, ‘there is a sort of invisible blanket between the world and me. I find it hard to take in what anyone says.’

Everyone has his/her/their own unique concept of death. Past experiences with death, as well as one’s age, emotional development, and surroundings, influence our own concept of death. Movies, television, and books are filled with images of death. Treating death as a part of life is difficult but may help alleviate some of the fear and confusion associated with it. Dealing with death must be done within your own beliefs and those around you.

Growing Around Grief

You may expect that after losing a loved one, your pain around their loss will eventually diminish entirely. Instead, grief may remain the same, but new life experiences help you to adjust to your grief. It’s ok for your grief to gradually feel smaller as you grow and continue your life around it. It doesn’t mean that your love for a loved one lessens, but that you can carry your grief with less weight.

What to do, what to say

Sometimes silence is good. Don’t feel a need to fill every moment with sound. Touch can say just as much as words, sometimes more. Simple actions such as making a cup of tea, leaving a bunch of flowers take on a new significance and can speak volumes. Whether you have been bereaved or are with someone who is losing their soul mate, child, or friend, then there are things that you can do to ease the pain. You cannot make it go away. This would deny us from being human.

Start the conversation

Don’t be afraid to talk about dying. If the other person doesn’t want to talk about it, they will let you know. Ask a question as an opener. Don’t be afraid to use the words death and dying. A good opener might be ‘I’ve been wondering about you since <<>> died. Would it help to talk? Or ‘I am wondering if you are frightened of dying’.

Clear up misunderstandings

Questions are good here, because it helps you understand a little more about how much the person knows about the situation. The answers may also surprise you and take you down a road, which you hadn’t considered. Don’t expect things to be cleared up in one conversation. It may take several, smaller moments – just make sure that the person knows it is OK to chat, whenever.

Listen for clues

Take your cues from the person and give only as much information as they seem to be able to take in or want to know. Everyone needs time to let things sink in – less is more. If they want additional explanations, they will usually ask questions about things they are wondering about. Children should be allowed to determine the pace of information that they receive. They will often set this pace without any prompting from you. They might ask questions that seem to come out of the blue, and then abruptly shift their attention back to a something else, such as playing. This may seem like the child doesn’t understand how serious things are, however, the child is pacing the amount of information, and taking the time needed to think about it. Reassure the child that you will give them regular updates as to what is happening and how the ill person is doing. Let them know that they can come to you (or another trusted adult) at any time with questions or to share how they are feeling.

brainstrust can provide counselling to help you. Click here for more

How children and teenagers view death

Infant

For an infant, death has no real concept. Infants do, however, react to separation from parent(s), painful procedures, and any alteration in their routine. An infant that is terminally ill will require as much care, physically and emotionally, to maintain a comfortable environment as any age group. Maintaining a consistent routine is important for the infant and their caregivers. Because infants cannot verbally communicate their needs, fear is often expressed by crying.

Toddler

For the toddler, death has very little meaning. They may receive the most anxiety from the emotions of those around them. When a toddler’s parents and loved ones are sad, depressed, scared, or angry, they sense these emotions and become upset or afraid. The terms “death” or “forever” or “permanent” may not have real value to children of this age group. Even with previous experiences with death, the child may not understand the relationship between life and death.

Preschool

Preschool-aged children may begin to understand that death is something feared by adults. This age group may view death as temporary or reversible, as in cartoons. Death is often explained to this age group as “went to heaven.” Most children in this age group do not understand that death is permanent, that everyone and every living thing will eventually die, and that dead things do not eat, sleep, or breathe. Death should not be explained as “sleep” to prevent the possible development of a sleep disorder.

Their experience with death is influenced by those around them. They may ask questions about “why?” and “how?” death occurs. The pre-school child may feel that their thoughts or actions have caused the death and/or sadness of those around. The pre-school child may have feelings of guilt and shame.

When a child in this age group becomes seriously ill, they may believe it is their punishment for something they did or thought about. They do not understand how their parents could not have protected them from this illness. This idea may make the preschool-age sibling of a dying child to feel as if they are the cause of the illness and death. Young siblings of dying children need reassurance and comforting during this time period, as well.

School-age Child

School-aged children are developing a more realistic understanding of death. Although death may be personified as an angel, skeleton, or ghost, this age group is beginning to understand death as permanent, universal, and inevitable. They may be very curious about the physical process of death and what happens after a person dies. They may fear their own death because of uncertainty of what happens to them after they die. Fear of the unknown, loss of control, and separation from family and friends can be the school-aged child’s main sources of anxiety and fear related to death.

Adolescent

As with people of all ages, past experiences and emotional development greatly influence an adolescent’s concept of death. Most adolescents understand the concept that death is permanent, universal, and inevitable. They may or may not have had past experiences with death of a family member, friend, or pet.

Most adolescents are beginning to establish their identity, independence, and relationship to peer groups. A predominant theme in adolescence is feelings of immortality or being exempt from death. Their realization of their own death threatens all of these objectives. Denial and defiant attitudes may suddenly change the personality of a teenager facing death. An adolescent may feel as if they no longer belong or fit in with their peers. In addition, they may feel as if they are unable to communicate with their parents.

Another important concept among adolescents is self-image. A terminal illness and/or the effects of treatment may cause many physical changes that they must endure. The adolescent may feel alone in their struggle, scared, and angry. Adolescents, similar to adults, may want to have their religious or cultural rituals observed. It is important for parents to realise that children of all ages respond to death in a unique way. Children need support and, in particular, someone who will listen to their thoughts, and provide reassurance to alleviate their fears.

How adults deal with death

Grief is a natural human response to the loss of a loved one. It can manifest itself in many ways. Grief moves in and out of stages from disbelief and denial to anger and guilt, to finding a source of comfort, to eventually adjusting to the loss. This process may not be linear, and it won’t be experienced in the same two ways. You may feel like you’re going backwards at times, the stages of grief may feel misaligned. However, this is all part of the grieving process, and it’s ok if yours doesn’t look the same as someone else’s. It’s important to reflect on what you need and give yourself space to navigate your grief at your own pace.

It is normal for both the dying person and the survivors to experience grief. For survivors, the grieving process can take many years and many forms. The challenge of accepting death and dying as the end stage of life is what the grieving process is all about.

Adapted from University of Virginia

http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu

Did this information make you feel more resourced, more confident or more in control?

Date published: 17-05-2009

Last edited: 01-2025

Due for review 01-2028