Anatomy and tumour types

The brain is the most complex organ in the body and is the organ about which we know the least. This page is to help give you a better understanding of how the brain is structured and the different types of brain tumour.

On this page you will find:

Coaching with brainstrust

Our coaching conversations are about collaboration, we will listen, listen some more, then ask questions. Our support specialists are trained to help you realise what matters most to you and come up with a plan to reach your specific goals.

Finding out about your brain tumour diagnosis leaves you feeling confused, panicked and overwhelmed. Book a coaching session today to start taking control.

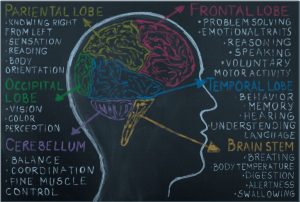

Basic brain anatomy

The brain is a complex structure. It contains millions of nerve cells (neurones) and their processes (axons and dendrites) in a highly organised manner. These are supported by many other cell types (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, etc). The brain is divided into several regions that have different functions:

The cerebrum is the largest area and is the source of conscious activity. It is divided into 2 cerebral hemispheres. The cerebellum is situated beneath the cerebral hemispheres and is connected to the brainstem, which in turn runs into the spinal cord.

Cerebral Hemispheres:

The left and right cerebral hemispheres control functions for the opposite side of the body. In addition, certain important functions (particularly speech and language) are located in only one hemisphere, called the dominant hemisphere. In right-handed patients this is virtually always the left hemisphere and in left-handed patients it may be either hemisphere (but is still often the left).

Each hemisphere is divided into 4 principal lobes and a hidden small lobe called the insula. The surface of the brain is folded with each crest being termed a gyrus and each groove between them a sulcus. The central sulcus separates the frontal from the parietal lobe and on each side of this sulcus lie the pre-central gyrus (in front) and the post-central gyrus (behind). The pre-central gyrus (motor cortex) is responsible for movement on the opposite side of the body and the post-central gyrus (sensory cortex) is responsible for sensations.

Brainstem:

All nerve fibres connecting the cerebral hemispheres with the cerebellum and spinal cord pass through the brainstem, controlling all functions in the limbs and body. There are also collections of neurones (nuclei) in the brainstem that control many functions in the head and neck, particularly eye movements, facial sensation and movement, swallowing and coughing. Areas within the brainstem also control consciousness, breathing, heart rate and blood pressure. So it’s an important area!

As these vital nerves all lie very close together in the brainstem, even a small area of damage might produce multiple severe deficits.

Below, is a description of what we know about the functions of different parts of the brain. However it’s important to understand that each lobe of the brain does not function alone. There are very complex relationships between the lobes of the brain and between the right and left hemispheres. But this does give you further indication of what might be affected by the position of a brain tumour:

Frontal lobe:

- Personality, behaviour, emotions

- Judgment, planning, problem solving

- Motivation, initiation

- Speech: speaking and writing (Broca’s area)

- Body movement (motor strip)

- Intelligence, concentration, self-awareness

Parietal lobe:

- Interprets language, words

- Sense of touch, pain, temperature (sensory strip)

- Interprets signals from vision, hearing, motor, sensory and memory

- Spatial and visual perception

Occipital lobe:

- Interprets vision (colour, light, movement)

Temporal lobe:

- Understanding language (Wernicke’s area)

- Memory

- Hearing

- Sequencing and organisation

Messages within the brain are carried along pathways. Messages can travel from one gyrus to another, from one lobe to another, from one side of the brain to the other, and to structures found deep in the brain (e.g. thalamus, hypothalamus).

Have you built your brain tumour team? Meet all the people that can help with the guide to ‘who’s who on your journey’.

Other brain words you might hear include:

Cranium – just a more interesting word for skull

Skull base – the bones at the bottom of the skull

Blood brain barrier – the mechanism by which the blood vessels of the brain prevent substances in the blood (such as bacteria) from reaching the brain. This is good, but can also work against the patient if vital anticancer drugs need to pass through this.

Glia – most of the brain tissue is composed of glial cells. Most brain tumours originate from glial cells.

What is a brain tumour?

A brain tumour is a mass of abnormal cells growing in the brain. The cells can come from the brain itself or from its lining (primary brain tumours) or from other places in the body (secondary or metastatic brain tumours). Primary brain tumours can be non malignant (benign) or malignant (cancerous). Secondary brain tumours are always malignant.

Size doesn’t matter… this is true. The size of a brain tumour doesn’t matter nearly so much as where it is located. A large, non malignant tumour may be easily accessible and therefore easy to remove. Or you can have a pea –sized tumour that is critically placed, and so makes treatment very difficult.

However, treatment options are developing all the time and one size doesn’t fit all. Some small tumours, in tricky locations, may be treated by radiosurgery and some large, diffuse tumours crossing the midline of the brain can be difficult to treat with radiation. So each case needs to be reviewed, discussed and options explored. It’s complex!

What causes a brain tumour?

No one knows. If we did, then we would be able to treat them more effectively, or even prevent them occurring at all. Some genetic disorders may mean that some people are predisposed to getting a brain tumour.

Classification and grading of brain tumours

All tumours in the brain can pose a threat to health. Benign tumours grow slowly and do not invade tissue, but they may put pressure on areas of the brain and cause problems. Malignant primary brain tumours spread into the healthy tissue and tend to grow more quickly than benign tumours. The World Health Organisation has developed a classification system for brain tumours. Knowing the classification and grade of an individual tumour helps to predict its likely behaviour.

Grading brain tumours

Grade I (low-grade) — the tumour grows slowly, has cells that look a lot like normal cells, and rarely spreads into nearby tissues. It may be possible to remove (resect) the entire tumour by surgery, but tumours in the brain stem cannot be completely resected safely.

Grade II — the tumour grows slowly, but may spread into nearby tissue and may recur (come back). Some tumours may become a higher-grade tumour.

Grade III — the tumour grows quickly, is likely to spread into nearby tissue, and the tumour cells look very different from normal cells.

Grade IV (high-grade) — the tumour grows and spreads very quickly and the cells do not look like normal cells. There may be areas of dead cells in the tumour. Grade IV brain tumours are harder to manage than lower-grade tumours. High- grade tumours can be difficult to treat.

Depending on their make up, tumours can be a mix of grades, so they will be defined by the highest grade.

Types of brain tumours

There are over 130 types of primary brain tumours. They are named according to the type of cells or the part of the brain in which they begin.

Below you will find a list of the more common types of brain tumours. This list is not exhaustive. If you are looking for information on a specific tumour type and can’t find it here, please email hello@brainstrust.org.uk

Meningioma

A meningioma is a brain tumour that arises in the meninges and is relatively common. Most meningiomas are slow-growing tumours, although some can grow faster. Meningiomas are generally non-malignant, although in a small percentage of cases they can become malignant and faster growing.

Acoustic Neuroma

An acoustic neuroma (also referred to as a vestibular schwannoma) is a slow growing non-malignant tumour which develops from Schwann cells. Acoustic neuromas account for around 8% of brain tumours and are generally found in adults.

Glioma

A catch all term for a range of brain tumours. These tumours arise from glial cells and can be non-malignant or malignant. They usually fall into three types: astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas and ependymomas.

Glioblastoma

A Glioblastoma, also known as GBM, or GBM4, is the most common malignant primary brain tumour. A GBM is a type of glioma. These tumours develop in the cerebral hemisphere and spread quickly into the surrounding brain. NHS treatment options include surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Tumour type specific information:

You can find more information related to specific tumour types here.

This area of our website will continue to grow with more information related to different types of brain tumours.

Defining brain tumours

Everyone with a brain tumour diagnosis should have access to accurate and reliable information and support that is relevant to their diagnosis. Part of this is to ensure that this information and support is only provided to people whose diagnosis is officially defined as a brain tumour. For us to support people with a condition that we know little or nothing about would be misguided; there is a risk we may misinform people and give incorrect information when there are other organisations better placed to do so.

To ensure accuracy, we use and refer to The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) classification system. This is a classification system that has been developed collaboratively between the World Health Organisation (WHO) and 10 international centres.

You can find more information about this here.

If you have been diagnosed with a condition and you are not sure whether it is defined as a brain tumour, please email us at hello@brainstrust.org.uk or call 01983 292 405.

Resources used in creating this page:

Patient/caregiver representative

Consultant neuropathologist

Consultant neurosurgeon

http://www.nice.org.uk/csgbraincns

Living with a Brain Tumour (Peter Black) 2006

www.cancercouncil.com.au/brain-cancer/

www.cancer.gov/types/brain/patient/adult-brain-treatment-pdq

patient.info/cancer/brain-cancer-and-brain-tumours

www.nhs.uk/conditions/benign-brain-tumour/

www.nhs.uk/conditions/malignant-brain-tumour/

Navigating Life with a Brain Tumour, L. Taylor, F. Alyx B. Porter, D. Richard (2013)

Did this information make you feel more resourced, more confident or more in control?

Date published: 17-05-2009

Last edited: 27-08-2025

Due for review: 01-2028

Help fund our mission

91%* of people told us that our information has helped them feel more resourced and in control.

A donation of £3 a month helps us keep this information up to date.

* 1712 out of 1883 respondents