Rowan is a mum of two, competitive horse rider and scientist. At the age of thirty-eight, Rowan was diagnosed with a Meningioma and her life was turned upside down. In this piece we tell Rowan’s story, from the worrying build-up to the diagnosis, to the strain of surgery, to finding her feet and her identity again during recovery.

Rowan fell in love with horses at three years old. Her mother had taken her to see them at a local riding school and once she’d set her eyes on them, she knew this was a love she would never outgrow. She worked extra newspaper rounds and waitressing shifts to afford riding lessons in her teenage years, and later pursued a degree in equine science and a PhD in veterinary preclinical science. It seemed nothing could stop her.

outgrow. She worked extra newspaper rounds and waitressing shifts to afford riding lessons in her teenage years, and later pursued a degree in equine science and a PhD in veterinary preclinical science. It seemed nothing could stop her.

But everything paused at thirty-eight years old when she was diagnosed with a brain tumour.

The realisation that something wasn’t right developed slowly with symptoms of fatigue, which she quickly attributed to her two kids, high pressure job, and demanding upkeep of competing with her horse. She’d always led a busy life, and it seemed like perhaps the burnout she had been warned about had finally caught up with her.

The realisation that something wasn’t right developed slowly with symptoms of fatigue, which she quickly attributed to her two kids, high pressure job, and demanding upkeep of competing with her horse. She’d always led a busy life, and it seemed like perhaps the burnout she had been warned about had finally caught up with her.

But then after one weekend horse riding, her eyes started to water. She felt a bit dizzy, and her neck became stiff. There was a weird crunching noise as she turned her head, and her arms felt strangely weak. It all seemed odd, but nothing extreme.

Rowan took her symptoms to her GP who presumed that her symptoms could be attributed to her competitive horse riding. She was diagnosed with mild whiplash over the phone and referred to a physiotherapist, but that didn’t seem to help.

Over the next few months she also began to notice her right eyelid drooping. It’s just ageing, she thought to herself, but the apparent asymmetry between her two eyes had begun to bother her, and she doubled down on the expensive anti-ageing eye creams.

The week before Easter, she developed a headache. She could pinpoint it to right above her right eye. Perhaps this was caused by eye strain, she thought, blaming the nagging pain on the multiple screens she used for work. But later that night it had developed into a burning migraine. It felt like her eye was on fire. Somehow, she managed to continue through a full day of work, alternating between optimistic doses of paracetamol and ibuprofen.

It felt like a fog had overcome her right visual field. Three days passed. She continued to ride her horse, competing, jumping, living her life, but all the while, she knew something wasn’t quite right. Whatever this was, it was here to stay.

She decided to call 111, who told her that she needed to be seen at the hospital. Surprised, her partner took her to A&E. Sitting there, she “just felt like a fraud. Looking around at everyone else who appeared sicker or in more dire need of medical care.” At nearly 4am, with a burning headache and foggy vision, she was sent for a CT scan.

Rowan was told that the results of the CT scan showed a mass in her head, and that she would need to be sent to another hospital with a neurology department where specialists would administer an MRI scan, and that surgery would likely follow. That’s it. She thought. My life is over.

The moment was world ending. What have I done? She wondered. What did I do to make this happen? Have I put my kids at risk? But she quickly moved into action. How can we make this work? You need to change your mindset. Don’t get worked up.

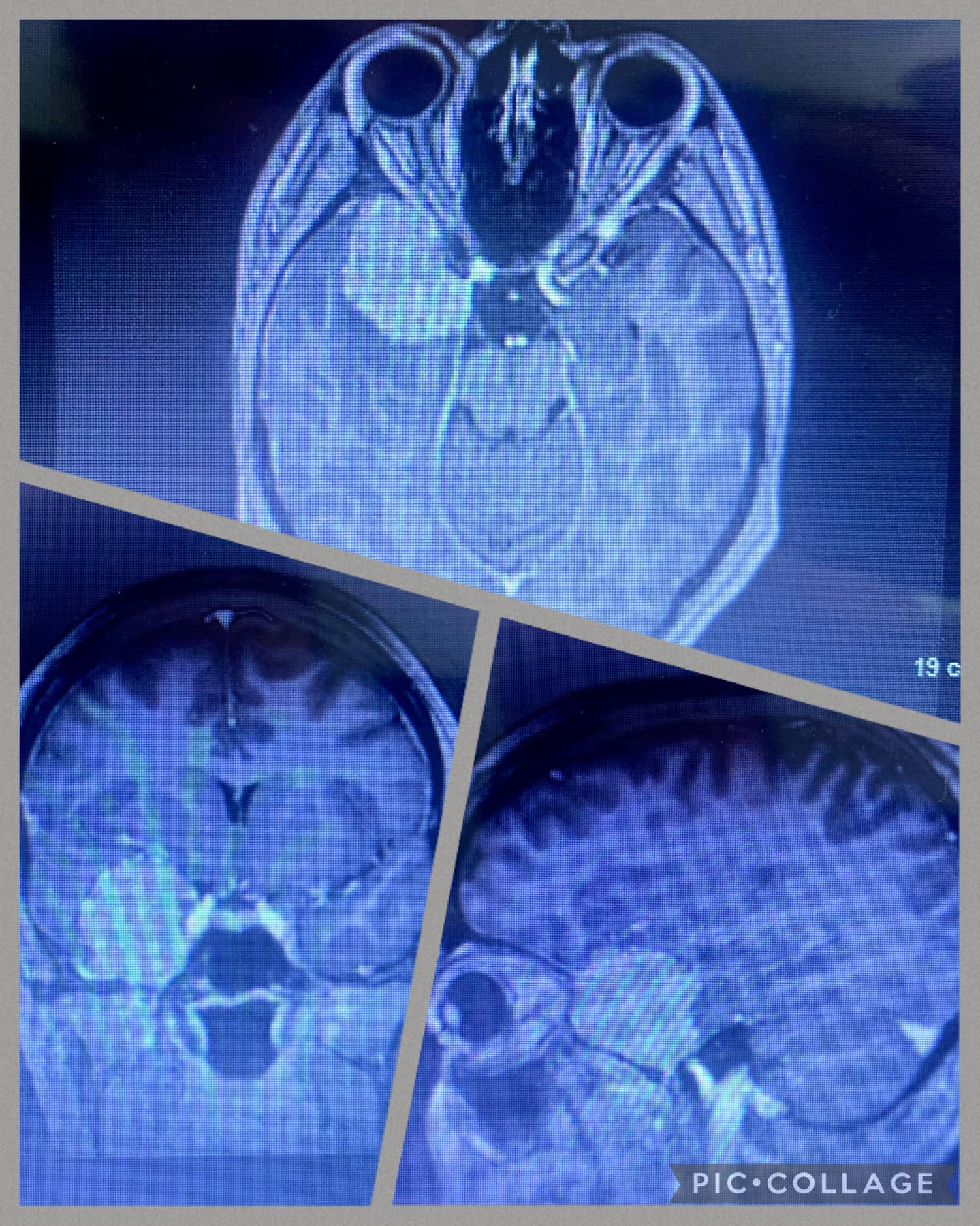

Rowan was taken in an ambulance to Leeds General, where she had an MRI scan in the early hours of Easter Sunday. Her surgeon began to describe the tumour to her – it was a three-to-four-centimetre diameter sphenoid wing meningioma, and it was pushing on her right optic nerve. There was no discussion of needing to watch and wait, the surgeon asserted they would be taking it out.

It turns out Rowan had been living with this tumour for almost fifteen years, but only began to present symptoms due to its size and the resultant pressure on her optic nerve.

In the weeks leading up to the surgery, Rowan prepared for the worst. She was afraid she wouldn’t come out on the other side the person that she was going in. That she wouldn’t be able to live her life the only way she knew how. That she wouldn’t be able to be there for her kids. She was worried about having a stroke, paralysis, memory problems, speech issues. She had begun to paint this picture of a brain tumour patient and couldn’t believe that that might be her.

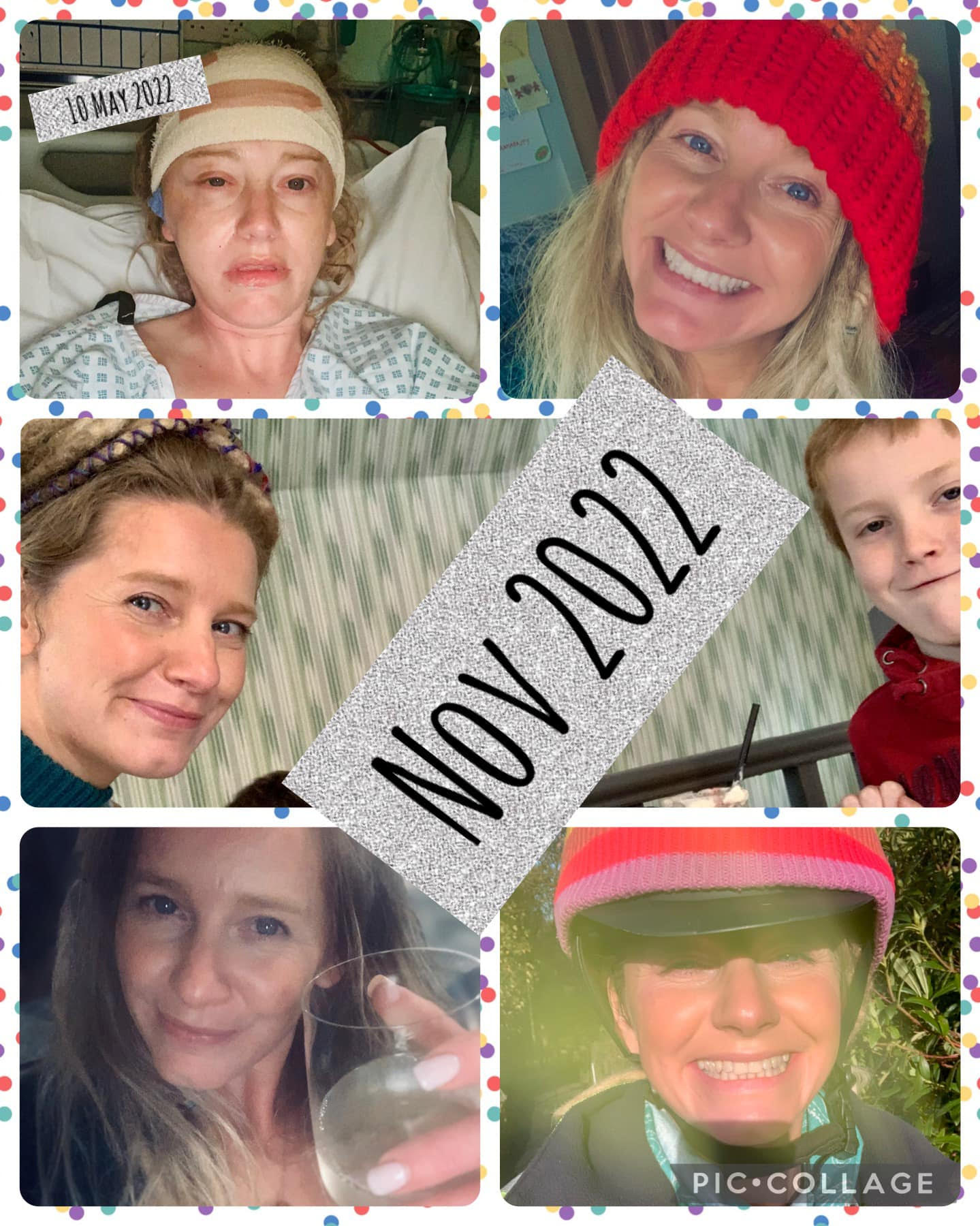

On the 9th of May, she was re-admitted. The surgery began with an embolisation, cutting off the blood supply to the tumour. The surgeries were successful, and the tumour was fully resected via a craniotomy on 10th May.

Having already been through an overwhelming few months, her recovery proved no easier. During the first operation on 9th May, her trigeminal nerve was damaged, causing her to lose normal sensation on one side of her face. She managed to retain motor control in the area, but lost all feeling, even on the roof of her mouth and her gums. After the surgery, she experienced immense swelling, dizziness, and strange sounds. Bright lights and loud noises were unbearable for weeks. The egg sized lump on her head where the surgeons had cut into her jaw muscle and skull seemed to only be getting larger, not to mention the unbearable wait for the histopathology results, which eventually confirmed that the tumour had been a Grade 1 (non-malignant) meningioma — a cause for small celebration.

After a few weeks, she checked herself back into A&E for testing but was assured that the swelling was normal and healing would take time. She battled on for weeks, unsure how she was supposed to learn to live like this.

Nearly eight weeks post-op, the swelling was relentless. Caught between dizzy spells, eyes she could barely open, and a rotating shift of ice packs, she knew something was wrong.

Nearly eight weeks post-op, the swelling was relentless. Caught between dizzy spells, eyes she could barely open, and a rotating shift of ice packs, she knew something was wrong.

And then on 1st July, the incision burst open and fluid began pouring out. It turned out that she did in fact have an infection. It was almost a relief given how unbearable the pressure was.

On the 2nd of July, Rowan had an emergency craniotomy, which was somehow more terrifying than the first. If the infection was within the jigsaw-like puzzle piece of skull they had removed, she would have to wait for a custom plate to be made – meaning yet another craniotomy. But they were able to wash and save the bone, and after this second surgery, she immediately began to feel more like herself. The swelling subsided as it should have the first time, and her vision and balance were restored.

Looking back on her symptoms, Rowan managed to maintain an admirable level of gratitude and sense of humour. She even kept a list of things that can’t cure a brain tumour —

- Expensive eye cream

- Lubricating eye drops

- Sinus medication

- Lavender and bedtime teas

- Taking five hundred photos of your face and eyebrows

- Rearranging your office for better Feng shui

- Baling twine (that fixes almost anything in the horse world!)

It seemed easy at the time to explain away her symptoms with life pressures, busyness, and natural ageing until it became clear that something was out of the ordinary.

And despite her worst fears of what it meant to take on the identity of a brain tumour patient, Rowan has begun to find her way back to herself. With a quiet tenacity, she’s developed a renewed focus on family and self-care. She’s found a way to centre her gratitude on the kindness and empathy of those around her. Her patient resilience is admirable.

And just a few months after surgery, Rowan has returned to being a mum to her boys, working, driving and riding her horse. It turns out, nothing can stop her.

If you or someone you love has a Meningioma diagnosis you can visit our Meningioma hub for more information and support. Alternatively, reach out to the support team on hello@brainstrust.org.uk or call us on 01983 292 405 and talk to a support specialists today.

Feel well-resourced and in control – sign up to our mailing list to receive all the latest news, events and resources straight to your inbox.